Part III: The who-pays-whom of real estate is not as simple as you might have thought…

All right, let’s go buy a house. I want to talk about the flow of money in a real estate transaction, and there is no better way of understanding that flow than wading right out into the middle of it all.

So let’s buy a house for $100,000. Where I live, in Phoenix, a hundred grand will get you a grungy dump. Where I grew up, in downstate Illinois, a hundred-thousand dollar house will put you among the diamond-crusted elite. Either way, it doesn’t matter. We’re not buying this house to live in it, but just so we can see who gets paid and how.

I want for us to buy this house with 100% financing — nothing down! — even though that kind of loan isn’t as easy to get as it used to be. Even better, I want you to take 3% of the purchase price as a concession from the seller to defray your closing costs. You’re going to have to put down an earnest deposit to show that you’re serious, but I like $500 for a house this cheap. Not only that, but, since there is going to be money left over from the closing costs concession, you’re actually going to get your $500 back at Close of Escrow.

Isn’t that cool? You just took possession of a $100,000 asset for not one red cent out-of-pocket. You bought a house for nothing. This is not a fantasy. I’ve done this for dozens of clients. But before you get on the phone to all your friends, telling them about your amazing financial skills, stop and think for a minute.

Did you just buy a house for nothing, or did you buy it by promising to make monthly payments for up to thirty — or forty — or fifty — years for principle, interest, taxes, insurance, HOA fees and private mortgage insurance?

Your lender pushed $100,000 onto the closing table, but he did it on the strength of your promise to pay all that money back and then some. In essence, you pushed a hundred grand onto the table, just as much as if you had paid cash-out-of-pocket for the home.

Who else brought money to the closing table? Unless it was a short sale — the seller was “short” the amount owed on his loan for the property — the only person who brought any money to the closing table was you. You even paid that 3% “contribution” from the seller, borrowing 3% extra so you could give it to the seller so the seller could give it back to you. Everyone sitting at the closing table — including you! — is going to get paid, but every single dollar of those payments will have come from your money.

Consider just that 3% contribution for closing costs. It’s a nice solution for buyers who have no cash, but it can also be a painless way to extract an extra 3% in discounted price from a seller who refuses to go any lower on the nominal purchase price. The buyers end up borrowing more, but the incremental interest costs on a loan they may hold for less than five years can be marginal compared to the utility of having 3% of the purchase price available as cash at the time they are moving. Everything is a trade-off, and a clever buyer’s agent can structure an offer in such a way that you get the best overall value in your current financial circumstances.

But suppose you were going to pay your own closing costs out of pocket. Would you have paid the same price for the house? The seller’s “contribution” nets out to a 3% discount on the house — actually a little less than 3% allowing for other costs. If you weren’t going to take this “contribution,” you would certainly offer less for the home. So if you had taken the “contribution,” who — in reality — would have paid your closing costs?

This little pantomime — you borrow more to give more to the seller so that the seller can give it back to you — is how we get this sleight of hand trick past your lender. If you are offering $100,000 with a $3,000 seller-funded discount, what is the actual value of the home? It’s $97,000, right? So why is the lender giving you $100,000 in the form of a 100% loan? Because the lender is affecting to pretend to make-believe that your $97,000 offer on the home is actually a $100,000 offer. The actual flow of money — from lender to buyer to seller and back to buyer — has no physical reality. There is no actual cash changing hands. It’s all bookkeeping notations. But by dancing precisely the right steps in a financial rain-dance, the lender pretends that 97% equals 100%.

But, guess what? We’re not talking about seller “contributions” for closing costs. We’re talking about the exact same pantomime when it is enacted to pay the listing agent’s and buyer’s agent’s commissions.

Who brought every last dollar to the closing table? Who is paying everyone who walks away from that table with money in his or her pocket? Except in a short sale, the buyer pays for everything.

So who is paying the agents’ commissions? The seller sets the gross amount of the commissions at the time the listing contract is signed. The listing agent and the seller set the amount of the buyer’s agent’s commission — including any bonus payments. But who actually pays those commissions?

I know of three different answers to that question.

The old-line brokers would argue that the seller is paying the commissions out of the accrued equity in the home. This is the accepted interpretation, and this is how lenders are able to justify the — to me absurd — pantomime of money-shuffling that is going on at the closing table. The buyer borrows $100,000 and gives it all to the seller. The seller give $3,000 back to the buyer’s creditors in the form of closing costs. Then the seller gives $7,000 to the listing broker, who in turn gives $3,500 to the buyer’s broker.

What’s the problem?

Do you recall that the lender, in order to swallow that whopper about the seller’s “contribution” to closing costs, had to make believe that 97% equals 100%? Try this on for size:

- The buyer believes the home is worth $100,000

- The buyer’s agent writes a contract reflecting a belief that the home is worth $100,000

- The lender originates a loan predicated on the belief that the home is worth $100,000

- The appraiser writes an opinion that that the home is worth $100,000

- The loan underwriter approves a loan for $100,000

- The title company prepares documents reflecting a purchase price of $100,000

But: The seller accepts $90,000 in trade for the home.

And: The lender is affecting to pretend to make-believe that the seller’s 90% is equal to the buyer’s 100%.

The “yeah, but” argument is that the seller has to pay marketing costs to sell the home. But clearly these are parasitic costs, just as the “contribution” for closing costs is parasitic. Fully ten per cent of the purchase price of the home reflects costs that do not add any value to the home. The buyer is borrowing ten per cent more than the home is actually worth in order to pay expenses that do not and cannot accrue as equity in the home. In my view, the lender is simply pretending that a home that is understood to have an actual value of $90,000 is worth $100,000 — all effected by sleight of hand bookkeeping.

At this point, objections will swarm around the idea of “market value.” The claim is that you will be obliged to pay the prevailing market value for the home regardless of how other costs are calculated. But, as we have seen, you would certainly offer less for the home if you were not taking the seller’s “contribution” for closing costs. And, if some benevolent charity were to offer to pay both agents’ commissions outside of escrow, you would offer even less. The seller might try to insist that you pay the prevailing market value anyway — in which event we would go buy a different house from a seller who understands the difference between gross and net — and how to hang onto a bird in the hand.

In fact, “market value” is twice a fiction. The only financial value any marketable item can have is the price agreed upon by a buyer and a seller. What we call “market value” is simply an educated guess based on recent very similar transactions. There is nothing that prevents you from offering $50,000 for our house, and nothing that prevents the seller from accepting your offer. The value of a home is what it sold for. Period.

Moreover, our idea of “market value” is clouded by the complicated lies the lender is telling itself. In other words, almost all recent sales will have been inflated from 5% to 10% by the imputation that real estate commissions and seller “contributions” to closing costs are expressions of the value of the home, when in fact they are parasitic costs tacked on by sleight-of-hand bookkeeping.

Note that I am not saying that real estate agents should not be paid for their efforts. Very much the contrary. If you’ve read this far, you understand that real estate is a complicated enterprise. Navigating a real estate transaction without representation is a poor idea. What I am saying is that the method we use now to document the flow of these funds is essentially a self-deception effected by the lender. The home isn’t worth $3,000 more because the seller is allegedly paying the buyer’s closing costs, and it isn’t worth $7,000 more because the seller is allegedly paying the real estate brokers.

Another way of thinking of who pays whom in a real estate transaction is to argue that the seller pays the listing agent and the buyer pays the buyer’s agent. This might be useful as a metaphor, but it is nothing but a pleasant fiction in our current circumstances. In the way the funds are accounted for by the lender and the title company, the seller is paying the brokerage commissions.

And, of course, from my point of view, the buyer is paying for everything. If the buyer is paying his own closing costs, he should offer less than if he were asking for a seller “contribution.” But since real estate laws are written to protect real estate brokers, not consumers, an unrepresented buyer cannot expect to extract a similar discount, even though this would be entirely reasonable.

This is a knot that won’t be untied, but the good news is, it doesn’t need to be. If we divorce the real estate commissions, we can do the bookkeeping in such a way that the seller definitely does pay the listing agent, while the buyer definitely does pay the buyer’s agent.

This is from an essay I wrote on this topic earlier this year:

To effect the divorced commission in the overwhelming majority of transactions, all that is necessary is for lenders to change their underwriting guidelines, making corresponding changes in the way they illustrate the flow of funds on the HUD-1 settlement statement.

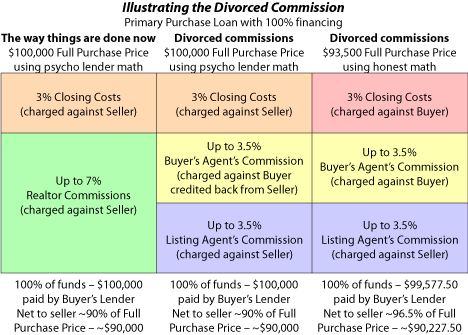

Right now, many lenders will allow up to 7% in sales commissions, to be charged against the seller’s side of the HUD-1, with up to 3% in closing costs, also charged against the seller’s side of the HUD-1.

If lenders changed their guidelines, such that no more than 3.5% could be charged against the seller for the compensation of the listing agent, with no more than 3.5% charged against the buyer for the compensation of the buyer’s agent, the commissions would be divorced.

So far, this is nothing more than a change in underwriting guidelines and HUD-1 accounting. Absolutely nothing has changed away from the paper-shuffling lender universe. The costs to the buyer and the proceeds to the seller are exactly the same.

Not to rock too many boats at once, but it would also be possible for lenders to make their internal procedures and the HUD-1 bookkeeping more honest, putting a little extra money in the pockets of both buyer and seller.

In the chart shown below, the first column illustrates the current procedure. The middle column shows how commissions can be divorced while retaining the psychotic style of accounting lenders currently deploy. The third column demonstrates how commissions can be divorced using accounting that is consonant with what is really going on.

Two points to take away:

First, divorcing the commissions will impose no new financial burdens on buyers. To the contrary, taking control of their agent’s compensation should empower them to pay less and/or get more overall value from their representation.

Second, in reality, divorcing the commissions can be effected simply and instantly, by the voluntary and unilateral action of mortgage loan underwriters. If they choose to insist on either column two or column three, as shown above, column one will be gone overnight.

And now it’s time for the lenders to issue a “yeah, but.”

“Yeah,” they will say, “but we will only loan against real property, not to pay the buyer’s agent or the buyer’s closing costs.” Which is to say the deliberately self-deceptive psycho lender math in column one is fine, but the exact same transaction expressed honestly — as a reflection of what is really and truly happening in real estate transactions all across America — is not acceptable.

This is absurd. The real estate commissions could be divorced tomorrow if lenders would insist on being told the truth instead of being willfully complicit in millions of new lies told every year.

The real estate commissions could be divorced tomorrow if the National Association of Realtors would impose a real code of ethics, one that forbade any member to participate in any real estate transaction where one party pays even one cent to the other party’s representative.

The real estate commissions could be divorced tomorrow if the Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development were to insist, via the RESPA guidelines, that the HUD-1 settlement statement reflect the actual flow of funds in a real estate transaction and not the inane lies the lenders insist on telling themselves.

In reality, the real estate commissions will be divorced when the Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission or a heavy-gaveled judge orders that they be divorced.

That’s a shame, because the rectitude of the matter is beyond all doubt. Some home sellers might want things to go on as they have, since sellers have such huge and unfair advantage in the present circumstance. Surely all home buyers, at least those who have read these essays, want for the commissions to be divorced at once. But we are each of us sometimes sellers and sometimes buyers, and our best long-term interests are served by creating compensation systems for real estate representation that are equitable — and that align “our” agents’ interests with our own.

This is but one of many salutary benefits that can be achieved by divorcing the real estate commissions. We will take note of some of the others in our next installment.

In Part IV: Not just benefits but salutary benefits…

< ?PHP include ("https://www.bloodhoundrealty.com/BloodhoundBlog/DCFile.php"); ?>

Technorati Tags: real estate, real estate marketing

JeffX says:

Where’s Ralph Nader when you need him…you should give him a call and appoint him head of the:

National Association of Former Associates of the National Association of Realtors…N.A.F.A.N.A.R.

Don’t know how old you are Greg, but you would have been one of Nader’s Raiders finest…

For what it’s worth, great (series of) post(s)…I wish more industry professionals and consumers would take the time to read this content, although I don’t see many getting past the 1st three paragraphs.

Too many people read to believe, not to think…

November 9, 2007 — 11:55 am

Mark A. says:

Please bear with me, as I’m still trying to wrap my mind around this concept of divorced commissions.

Say for argument’s sake, an agent represents seller S in the sale of his property. Unrepresented buyer B comes along and wants to purchase S’s property. As an aside, in my state, real estate laws are written with the intent of having ALL parties in a transaction be represented. Incidentally, B doesn’t care about representation and just wants to buy S’s house. In a divorced commissions scenario, B would have to compensate the listing agent for representation, but B doesn’t want to pay any buyer’s broker fee. Will B be out of luck, trying to buy S’s house, or will she become a FPBB (for purchase by buyer), with whom the listing agent will have to work (through many problems) throughout the transaction, just as though she were a licensed buyer’s broker?

November 9, 2007 — 12:11 pm

Greg Swann says:

I’m lost in all the initials.

The way things are right now, an unrepresented buyer would pay the buyer’s agent’s commission to the listing agent even though he derives no benefit from the listing agent. If the commissions were divorced, the seller would pay the listing agent, but the buyer would not pay for any representation, nor would he receive any.

In reality, a smart unrepresented buyer would purchase real estate advice a la carte, as needed. One of the huge defects of the buyer’s agent’s commission being paid as a percentage of the sales price by the listing agent is that buyers are forced to buy a pay-one-price product. Some people need and use a lot of their agent’s time. Some people are better-informed and much more efficient. The way we do things now is completely contrary to the principles of capitalism.

November 9, 2007 — 12:28 pm

Jay Ovalle says:

These intellectual exchanges are fascinating and an interesting exercise in subjectivism, but deep in the trenches only the pragmati thrives. It has been my experience that buyers don’t really care how or how much you get paid as long as you deliver the goods: the home they want. Most will drop you on a blink if they find their home without you. They will not care one bit about agency or how much work or expense you have incurred on their behalf, schlepping them across town for days on end. They are only loyal to their need. Excuzes my icy cynicism, but I am sure, is not greater that the one the consumer expresses for our industry. “Ground control to Major Greg…”

November 9, 2007 — 1:04 pm

Mark A. says:

“the buyer would not pay for any representation, nor would he receive any.”

This is one of the components of this discussion that deserves some more thought. The reason most states abandoned sub-agency and implemented buyer agency was (so we’re told) unhappy buyers who felt they needed exclusive representation. Divorcing commissions goes beyond revising NAR’s Code of Ethics. State laws need to be re-written to reflect a broader choice for real estate consumers, not to mention a complete overhaul of RESPA. Assuming this goes well, now consumers need to be re-educated: Guess what, you can still be represented exclusively, but you gotta pay for it.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s an intriguing idea (divorcing commissions), but it’s a Herculean task at hand.

November 9, 2007 — 1:19 pm

Ryan Ward says:

Wow! That is a very complicated answer to the question. Here is a different one and easier to wrap our heads around:

All of those costs are negated because they were paid the first time the house sold. So, the “value” of a home includes services provided by real estate agents and associated costs because they are included in the initial “value” of a home.

Except for the closing costs. 🙂

They are not extra.

November 9, 2007 — 1:57 pm

Matt Pellerin says:

Good to hear your take on this Greg. I remember back when I started and the industry had just moved away from Subagents of the seller to buyers agent. There were agents that just couldn’t accept the “change” they percieved.

This shift will require the same type of pain for those who unwilling or unable to look forward. But, IMO it is the way our profession needs to head in order to further protect and empower the buyer.

November 9, 2007 — 2:04 pm

Benn says:

So, to sum up this page.5 of words, you want more dual agency, right?

November 9, 2007 — 2:50 pm

Bob says:

Here’s my take:

At the end of the day, the buyer brought $100k to the table and walked away with an asset worth $100k. The seller brought a $100k asset to the table and walked away with $94k.

Spin that.

November 9, 2007 — 4:27 pm

Greg Swann says:

> At the end of the day, the buyer brought $100k to the table and walked away with an asset worth $100k. The seller brought a $100k asset to the table and walked away with $94k.

You’re reading it wrong.

The buyer paid $100,000 to take possession of an asset that, upon immediate resale under the same terms, would only yield $90,000.

There are costs associated with every acquisition. What’s wrong with the way we do things now is that the buyer is paying costs over which he has no control and none of this is disclosed to him. To the contrary, we tell the buyer an elaborate series of lies through the whole process.

> Spin that.

I’m not spinning anything. I’m illustrating how we can make an honest business out of what has until now been a conspiracy against unknowing consumers.

November 9, 2007 — 5:18 pm

Ryan Ward says:

So how do you suggest it be resolved because if it sells for $100,000 and you have the buyer pay an agent their side and the seller pay their side, the buyer pays over the 100 and the seller nets under 100.

The whole point is moot as real estate sales values have the costs of the transaction “built in” to the value of the house. The market value includes sales costs. It always has ever since the first house sold and now it is simply a factor that determines the value.

Noone is being hoodwinked and it’s completely honest.

To me this is a non-conspiracy. It’s readily transparant and everyone can see it for what it is. This isn’t voodoo. It’s simply a matter of whether you want to call it six or a half dozen. To break the costs out of the contracts would in fact be the one and only time that the “value” would have to be adjusted. From then forward, it would be exactly as it is now – except the costs would show on a seperate line.

The costs remain the same – that’s why the value remains the same.

November 9, 2007 — 6:33 pm

Ryan Ward says:

Furthermore,

Just because the buyer would lose $10,000 if he turned and sold does not in any way mean that the value is not still $100,000. It simply means that you have to pay for services if you want to sell your house.

November 9, 2007 — 6:47 pm

Tim says:

Outstanding article.

One of the things kind of lost in all the flury of the last few years flooded with 100% nothing down transactions is that, um, in EVERY one of the transactions our office closed with 100% financing, the purchase price was increased over an above the list price to offset those closing costs paid by the seller(tongue in cheek). Making matters even more dizzying was the 100% borrower involved in multiple offers. And, thus, here we sit today with perlexed looks on all our faces as to how come things are what they are.

Speaking from purely an escrow perspective and bias, it sure would be neat to divorce escrow fees from being earned only if a transaction closes. And,I suppose if you take the intent of your article at face value, buyers just pay for, like, everything…even the entire escrow tab although the HUD says the seller paid their fair share. In my view, escrow co’s only being paid if a deal closes kind of defeats the purpose of the spirit of neutrality—-never mind the problems inherently created if the escrow boss/owner of the escrow co. is the Real Estate Broker or Mortgage Broker directing “traffic” (purchases or refi’s)to the escrow office.

November 9, 2007 — 7:39 pm

Al Sloviski says:

Greg

Great post. I think you are on the right tract. Letting the buyer see the true cost can only clean up transactions. Putting the buyer in charge is the only real honest way to set service value.

The one question I have is how much time did you spend on that post? If it was me it would probably have taken 8 hours. You seem to have it down so I will assume it took around 2 hours. That seems like a decent amount of time to spend/waste.

You seem to post frequently. I would assume that you spend at least 30 hours a week on this blog. It may be at midnight or at lunch, whatever. You seem to have a following and it looks like you have created something unique. I am sure you are respected by realtors nationwide. You are helping their businesses grow.

If I was a client I would be impressed. I would be happy to tell all my friends what a great realtor I contracted with. The problem is that I would want exceptional service for a reasonable fee.

If I had to pay all of the fees related to a transaction based on transparent dollars I might not hire you. I would probably hire someone who is a full time professional, not part time.

Be careful of what you wish for.

November 9, 2007 — 9:48 pm

Bob Wilson says:

>Just because the buyer would lose $10,000 if he turned and sold does not in any way mean that the value is not still $100,000. It simply means that you have to pay for services if you want to sell your house.

>I’m illustrating how we can make an honest business out of what has until now been a conspiracy against unknowing consumers.

That assumes the same terms and a specific set of market conditions.

In the last market, aside from title and escrow costs, many sellers didn’t have to pay for services to sell and their buyers only paid their respective costs. There were no additional costs, just immediate profit.

>I’m illustrating how we can make an honest business out of what has until now been a conspiracy against unknowing consumers.

Admirable goal. I would start with the listing commission, the ability of a buyer to elect for NO representation, and the mls structure.

November 10, 2007 — 8:57 am

Cathleen Collins says:

Al Sloviski,

Like Julie Brown, you like em big and stupid, eh?

You over estimate the time this blog takes away from Greg’s work, and under estimate the value that our clients place on thoughtful representation.

November 10, 2007 — 10:19 am

Charleston real estate blog says:

Greg, I’m enjoying the series. As to Al S, you get what you pay for, choose wisely.

The buyer who does much of the work should pay less and the buyer requiring significant handholding should pay more. You can only accomplish that by divorcing the commission and charging buyers for the level and quality of service you are being asked to provide.

November 10, 2007 — 1:42 pm

Al Sloviski says:

“You Must like them Big and Stupid”

I am not sure where you are going with that statement but I guess I am pretty big and?

I don’t have an argument with the Thesis Greg created here. In fact the information I just read makes complete sense and should be implemented immediately. The NAR should adopt it tomorrow and the world should change by Tuesday. It is not my point to disagree with his theory; it is to question the use of his resources.

I am sure that Greg has opinions about Darfur. Why not spend week writing about the injustice to the world. I am sure he would prove his point and back it up poetically. Where does that get you? It may get you an award or a paper weight to put on top of your internet hosting bills. I am not sure it will get you any business.

Real Estate is local? As in when he sells something it is local. When he gets paid it is local. It appears that most of his resources are being spent on macro exposure. If he is looking to set up a bed and break feast in phoenix I am sure he could fill it with traveling realtors. I would suggest if he does that to take cash only or at least 10% down with proof of income.

Good intentions are great, notoriety could even be better. Probably the best thing is a wad of cash in front of both those things. If you are independently wealthy and this is a hobby, excuse me for noting the obvious. If you are in the trenches more resources might be better spent locally.

I think I will take Greg’s last mantra and quote it in a bar. I might have a smaller audience but the drunk next to me might want to buy a house. If I get a sale or listing I will give credit to Greg and this blog. Maybe you can get a three day weekend at the B&B.

Al

November 10, 2007 — 10:14 pm

Brian Brady says:

Greg:

As you know, I mostly agree and am thrilled with this series. Your argument, however, that it is the lender’s responsibility to solve this mess, fall short on cash-paid transactions.

It is impractical to expect the banking industry to protect a buyers interests; that’s the real estate broker’s job. That duty to protect a buyer, cash or financed, always falls to the fiduciary.

Lenders will always make what they believe to be rational decisions. Allowing a buyer to finance the costs of real estate representation is accepted as rational. Divorcing the commission is a brilliant idea. Lenders will follow, once it is explained.

No, this problem is all yours (real estate brokerage). We (lending community) have already agreed to finance real estate brokerage commissions; you have to figure out how to properly charge them.

How can you change this mess and get lenders to understand? Try a transaction the way you insist. It’ll take a unique and courageous originator to champion your cause and an extra 2-3 weeks for the COE for the lender’s attorneys to fully approve it.

I know three originators who are up to the task…so do you.

November 11, 2007 — 11:11 am