We live and work right on the Arizona Canal in North Central Phoenix. North Central is a nebulous geographical region. Properly speaking, it runs from Seventh Street to Seventh Avenue, Missouri Street to the Canal. Within those boundaries, you will find some of the most prosperous and powerful people in the city — two categories from which we are more than amply excluded.

People living as far east as 16th Street and as far west as 19th Avenue might claim to live in North Central, and it would be considered churlish to contradict them. But this courtesy would not be extended to anyone living north of the Arizona Canal. North of the Canal is Sunnyslope, one of the worst neighborhoods in Phoenix.

What’s the difference? About $150,000 right now. In other words, the house you could buy just north of the Canal for $250,000 would cost you at least $400,000 if you were to buy it just south of the Canal. Location, location, location.

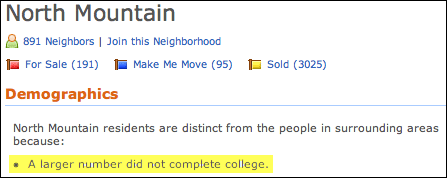

Now suppose you have joyfully paid that price premium to own, use, enjoy and profit from a home in North Central. If you went to your neighborhood page on Zillow.com, what might you not want to see?

I added the highlighting, just to put a finer point on the slur. In fact, this is just the kind of ham-handed stupidity you would expect from a robo-bartender, which, if you think about it, is one of the bogus roles a social network can take on.

Full disclosure: I am a social networking skeptic. The youthful fetish clubs are immensely popular with people who are determined to stay forever young. The commerce-oriented sites are full of self-promoters, every bit as interesting as the Friday morning business card exchange at the Denny’s over by the freeway. It could be there is something else I’m missing, but I’m not predisposed to care.

The truth is, I’m an introvert, as are many smart, technically-oriented people. My skin doesn’t actually crawl when I’m around other people, but my social interactions are always project-focused, and I’ve never been to a party that I didn’t want to leave before I got there. In this way, the idea of social networking is funny: The aggregations of people who don’t aggregate in real life.

There are things that other people do that mean nothing to me: “Gettin’ together.” “Kickin’ back.” “Shootin’ the breeze.” I understand these things in the abstract, but they’re not activities I would ever undertake by my own unfettered choice. In fact, I really enjoy being social with people in whom I have taken a project-focused interest, but even with my wife and kid I am rarely without agenda.

I’m actually painfully aware of this, because we have been chipping away at a sculpted model of what a truly functional community-oriented weblog would look like, and the more defined that image becomes, the more I realize how ill-suited I am to the task I am defining.

“You want to go where everybody knows your name.” What’s more of a community than the regulars at “Cheers”? With respect to Teri Lussier’s weblog, we’ve talked about chatting over coffee, another warm and fuzzy kind of community. If you can build a community of people who like you and each other and who like to get together with each other, you will have built what we have been talking about here.

But I will probably not build such a thing. The idea of hanging out in a bar, doing nothing but impairing my brain, does make my skin crawl. I don’t see myself being very good at any virtual analogue of that sort of thing.

And yet… I know that the kinds of ideas we are talking about — building persistent communities of interested end-users — will work, because this is exactly what we have done here. We are project-focused to a fault, but this is what provides the meat and meaning to our social interaction. We cavort as only introverted nerds can, finding delight in self-improvement, exploring the interstices of each other’s minds.

Now consider that there are thriving communities of interesting, productive people working together all over the internet — and not just in self-consciously Web 2.0ish sites. This morning Joel Burslem pointed to the Real Estate Webmasters’ Forum, home to tens of thousands of posts. I have many, many old friends at the Desktop Publishing Forum, itself a revivification of an eponymous community on CompuServe. Even now, there are very active groups on Usenet that have been going strong for decades.

Why do these work where so many self-consciously Web 2.0ified wannabe communities fail? The first reason is obvious: Whether introverts or extroverts, the members of the community identify their own self-interest in their on-going participation with the group. For project-focused introverts like me, learning to do more work, better and faster, is a very strong incentive to social interaction — especially since I get to be alone when I’m doing it!

But there is another factor that I think is even more important to understanding successful internet-based communities of interest: The ones that work, long-term, seem to afford the individual end-user a very high degree of control. Even if content is moderated — as it often is, except on Usenet — users have the power to initiate new threads, new meta-topics, new paradigms.

Active Rain is a good example. Users have the power to create their own little worlds within the Active Rain universe. I think it misses the mark as a marketing tool, at least for Realtors, but the whole community hangs together beautifully.

Forum software offers the same kind of relatively free creative control. Forums themselves are visually disquieting, and they’re written in antiquated HTML. But a user can easily split a digression off into another thread. With the right permissions, users can create new topics or even new topic areas. Empowered users can grow the community in the direction of users’ interests.

Weblogging is perhaps the best available example of spontaneous community-building through empowered collaboration. Registered users can create new content at will, but even unregistered commenters have significant content-creation power. And anyone can create a new weblog at any time.

What does all this have to do with Zillow.com?

I think they’ve made a mistake in their approach to community building, a mistake that will prevent a true community from emerging from all their efforts.

As an example, what is a neighborhood? It’s not what Zillow says it is, and it’s not what some city council says it is. A neighborhood is what the neighbors say it is, and, as in my North Central Phoenix neighborhood, neighbors can differ about what the neighborhood really is.

So how should Zillow define the neighborhoods it hopes end-users will create content around?

It shouldn’t. It should let the users define the neighborhoods, and if there are different interpretations of what the neighborhood is, it should allow the proponents of those different ideas to create multiple competing neighborhood descriptions. When one starts to draw all the attention and the other fades away, Zillow can snuff the loser. Until then, the neighborhood advocates will have an investment in creating content for Zillow, and an avid interest in getting their friends to the site to show off what they have created.

In other words, they will have created a virtual analogue of their neighborhood as a means of defining and describing it. This is an atom-sized on-line community, an acorn from which a great oak can grow.

I think Zillow should have implemented weblogging, not the forum structure it has deployed. Why? Because self-selected webloggers (c’est moi!) are invested in creating compelling content and in showing it off. Again, we’re talking about recruiting interested parties who will in their turn make an effort to recruit an audience.

Even going with forum software, I would that Zillow had gone with off-the-shelf technology for the reasons I named above: Empowering users to split off digressions or to create new topics or new topic areas.

Successful social networks have a de facto middle management structure. Regular users have powers commensurate with the responsibilities they have taken on. In seasoned weblogging and forum software tools, these management levels are built in. Administration of a successful internet community is too much work for one person, but sharing the responsibility for the community also multiples the number of people invested in the success of the community.

This is what Zillow.com should be aiming for. The current hierarchical structure is Duke and serfs, Alcalde and peons, with no significantly-invested middle managers to build and sustain a community. The site offers incentives for participation to Realtors and Lenders, but all that has come of that is the business card exchange. Without greater opportunities for control over their own expression, there is no compelling reason for ordinary people to make Zillow.com their primary home on the internet.

Why would Zillow want to relinquish the kind of control necessary to make its software offerings attractive to the unwashed masses of self-selected soap-boxing pontificators? Because it’s in the business of selling eyeballs to advertisers. The more eyeballs there are, and the longer they stay, the more money Zillow makes.

What makes a town a community and not a ghost town are neither the structures nor the people. A community is composed of the persistently and freely proffered energies of the people within and among those structures. Zillow can provide the agora, the forum. But if it tries to circumscribe too tightly what can be done in its town square, it will fail to engender a community.

The truth is, I don’t know if this can be done at all. Successful internet-based communities are composed of people who are continuously self-interested in the business of the community. There are subsets of the real estate market to whom this applies — professionals, investors, remodeling/refurbishing hobbyists — but these already have successful on-line communities. Whether the larger market of homeowners is willing to attend to some aspect of real estate on an enduring basis remains to be seen.

But: If they do want to talk, they’re going to talk their own way, not Zillow’s. If Zillow wants them to talk in its marketplace, it has to get out of their way.

Technorati Tags: disintermediation, real estate, real estate marketing, Zillow.com

Brian Brady says:

Your analogy of social networking to a business card exchange at Denny’s is accurate. I want to be the PRESENTER at the Chamber of Commerce meeting, not the insurance agent panhandling business cards.

Counting my drinks while someone else is selling is not my idea of a fun 90 minutes. Zillow’s Real Estate Guide is exactly that. Too many rules. Too many de facto judges they call industry mavens.

There is nothing worse than writing a beautiful Zlog to have it torn apart…errr…edited… by the Zillow mortgage “expert”, preaching 1974 economics, the next day.

Zillow would do well to embrace opinion from industry professionals rather than trying to sanitize the brokerage of property process. Zillow’s problem is they just don’t understand real estate and mortgage brokerage.

July 12, 2007 — 12:28 am

Artur Urbanski says:

Greg, I spent last few hours reading your posts. I started with Zillow’s agent ranking and than was caught in reading many of your other posts. They all read very well. I agree with many of your points, but not all. I would love to point you to a few of my posts, but it looks as Bloodhounds readers cannot create links (or I have not figured out how!).

I am currently writing another post on my view of MLS evolution. While I see a lot of MLS faults, I am not convinced that “cutting the branch we all are sitting on” is the best solution. These days, I believe in evolution not revolution and a lot of your statement (again it is a pleasure to read your posts!) see to advocate annihilation of real estate associations and MLS. Yes, I see many problems with the current system, but also see positive elements of their work and their impact on consumers (emphasis on ethics, quality, etc). At the same time, as every good monopoly, realtors associations and MLS are slow to change. Zillow and Trulia made them realize that change and adaptation are the only way forward. I see positive changes in some extremely conservative associations that happened within last 6 to 12 months I haven’t seen for years. Are these changes enough to save MLS? I am not sure. In my post “Who started real estate revolution?” I credited Zillow and Trulia for being a visible trigger of this revolution. At the same time, I don’t see Zillow, Trulia or Redfin as Realtors benefactors(I know – Realtors might be dying brand!). And why would I want to save Realtors? Yes, I am an agent and Broker/Owner, but have 25 years experience in technology R&D. Wouldn’t be easier for me to jump on the real estate technology bandwagon? It is not that I have not thought about it. But learning my new profession I understood that Realtors and Brokers hold the key to the real estate future and not the technology start ups, doesn’t matter how well funded. Yes, start ups “can trigger changes”, but the final say is up to brokers and agents. Why? Because they have the knowledge and this is what clients want — real knowledge. Real estate is changing. Average commissions will get lower, long awaited new business models will arrive, but good brokers and good agents will not go away. Yes, there will be many casualties among our ranks, but at the end (five years from now?) the best agents and brokers will become real state consultants (in many different flavors…), meaning that they will provide more knowledge and expertise to clients for less money. The average commission will definitely be lower than today, but I strongly believe that some of us will be still having commissions above 6%. I will not venture to predict what might happen 10 years from now, however. But let me come back to the “branch we are sitting on”. Why shouldn’t we cut it? Because we need a counterbalance. We need “Trulias” to put enough pressure on MLS to change, but without a counterbalance it might be more like a “cultural revolution” and new “business masters” will “eradicate” realtors before acquiring their knowledge!

Greg, would it possible to share more of my ideas at this forum? Please let me know.

July 12, 2007 — 3:13 am

Drew Meyers from Zillow says:

Brian-

Please note the real estate guide (which is a wiki) is VERY different than a blog. Since wikis are collaborative, no one person “owns” any of the content. That’s just the nature of wikis – someone stubs out an article and others collaborate on it over time to make it better.

Zillow is certainly thinking about other ways to let industry professionals voice their opinions — I’m all ears if you have feedback as to what you think we should build to help solve this problem.

July 12, 2007 — 8:22 am

Greg Swann says:

Artur, to encode a link in a WordPress comment, just do it the way you normally would. Even simpler, just paste in the URL. WordPress will code it for you. Ugly but very fast.

July 12, 2007 — 8:40 am

Brian Brady says:

“Since wikis are collaborative, no one person “owns” any of the content.”

Drew, this is what I mean about “rules”. Zillow would do well to understand that you have eliminated industry participation BECAUSE of that “rule”.

Greg hit the nail on the head when he suggests that blog platforms would attract professional participation. The Ziki is a great idea to gather content but you’re letting people who don’t understand the business edit expert advice. Zillow’s credibility with the professional community is lacking because of it.

July 12, 2007 — 9:25 am

Todd Carpenter says:

A local newspaper here in Denver operates a business model that Zillow would do well to check out. YourHub let’s people start blogs, but they have also hired many part time, or entry level journalists to contribute. If Zillow were to employ some local “experts”, they could really jump start start the content for individual neighborhoods, and get feedback on better defining these neighborhoods.

In Denver for instance, Bonnie Brae in missing, and Highland Park is a separate neighborhood to Highland Potter. In addition to LoDo, there’s LoLoDo. Plus other neighborhoods are missing like Governer’s Park, Old South Pearl, Ballpark, and Curtis Park, and possibly the most populated neighborhood of all, Down Town Denver.

None of the communities listed on Zillow cover Down Town. In many cities, “Down Town” would be a collection of smaller neighborhoods. In Denver, it is a neighborhood. Hiring an someone local to each of the bigger metro areas would know that.

July 12, 2007 — 10:49 am

Rob Green says:

Gregg,

I have thoroughly enjoyed your posts with many of them ringing truer to me than others. But I must say that this post is one of the very few with which I can personally identify, unfortunately. 🙂

“The truth is, I’m an introvert, as are many smart, technically-oriented people”

“I really enjoy being social with people in whom I have taken a project-focused interest, but even with my wife and kid I am rarely without agenda.”

The thing that I find encouraging about that for all of us audio/visual squad members, is that this blog is a vibrant validation of the power of the socially reticent to not only survive in an industry which has been based on “schmoozing” ability, but also the validation that we can thrive in such an industry as well.

When I first started in this industry I struggled a great deal because, I am not, by nature, a salesperson. I have always functioned more as a consultant, which my clients have loved, but getting those clients initially proved cumbersome. Over time, I have been blessed with referrals from those clients and so I don’t struggle like I used to.

But, it’s always good to hear about the success of other socially-reticent people. So, thanks again for the encouragement.

In regards to your comments about Zillow’s constraints on building community micro-blogs, it seems to me that their approach is reminiscent of the stereotypical social studies teacher in the 50’s and 60’s who smiled and told the students to just trust the government’s leadership and be a happy follower. However, in reality, this country’s government was founded upon the wiki principle through the codification of prevailing thoughts at the time. It was the combined, unregulated opinions of the people at that time that gave birth to the greatness of the country we enjoy today.

In reality, almost all compulsory opinion-regulation is fated to be replaced by venues that offer a more free exchange of ideas and are relatively independent of top-down decrees (i.e. the fall of communism, the Berlin wall, etc).

I’m willing to bet that the Zillow community microblogs will be popular for awhile, but they will eventually loosen their restraints for a more accurate Wiki experience as their users will demand, or they will create more of their own blogs which will spread by word of mouth, the most powerful marketing medium.

July 12, 2007 — 11:17 am